The question of whether Jesus of Nazareth ever truly lived has long fascinated scholars, skeptics, and believers alike. Yet, while we may never know every detail of his life, several elements—most notably his baptism and crucifixion—are widely regarded as historically credible. It is implausible, for instance, that the early Christian community would have fabricated a humiliating death for their supposed Messiah, especially one as ignominious as crucifixion.

But if we look for hints, what he may have looked like, the historical record is far from complete. There are no inscriptions, skeletal remains, or direct archaeological evidence tied explicitly to Jesus. At least not, if we doubt the shroud of Turin.

We know what he taught (and even that was most certainly subject to later embellishments), yet we remain uncertain about who his teachers were. Stories surrounding his birth—such as the notion that King Herod would order a massacre based on the birth of a child in a rural village— strain credulity from a historical point of view.

Yet, to be honest, the lack of archaeological evidence is neither surprising nor exceptional. Jesus, according to tradition, was a carpenter—a member of the lower class—not a king or military leader. In fact, we have virtually no archaeological traces of anyone from Jesus’ social milieu. The absence of physical evidence does not imply nonexistence; it merely reflects the historical anonymity shared by most people of his time (and ours, so to say).

Even other more prominent figures from antiquity are not archaeologically well-documented. We know little about Pontius Pilate, and Caesar’s wife, Calpurnia, vanishes from the record after his assassination. Berenice, the Judean queen and mistress of Emperor Titus, disappears from history after leaving Rome. Their lives, like Jesus’, are preserved primarily through scattered literary references rather than physical remnants¹.

Nonetheless, aspects of the New Testament’s historical context have been corroborated archaeologically. In Nazareth, a stone-carved courtyard house with graves and a cistern has been unearthed, and it is conceivable this could have belonged to Jesus’ family. Physical evidence for Roman crucifixion practices has also emerged: in 1968, archaeologists in Jerusalem discovered the heel bone of a man with a nail still embedded in it—a rare but direct testimony to the brutal method of execution Jesus is said to have endured².

There is also textual evidence for Jesus beyond Christian scriptures. While the New Testament remains our most detailed source, it is admittedly written by believers and shaped by theological motives. Still, also the Roman historian Tacitus refers to “Christus,” who “suffered the extreme penalty during the reign of Tiberius at the hands of one of our procurators, Pontius Pilatus”³. The Jewish historian Josephus, writing around 93–94 CE, equally makes two references to Jesus in Antiquities of the Jews⁴.

Taken together, these traces—textual, contextual, and cultural—support the conclusion that Jesus was a real person who lived and died in first-century Palestine. It is therefore reasonable to investigate what kind of life he led and how he looked like.

What might have been Jesus’ daily Life and Appearance?

Scientists hence today seek to understand the historical Jesus and his material world. Although Jesus’ physical appearance is never described in the Gospels, one can infer that he looked ordinary enough not to stand out.

This is implied in several narratives. When soldiers come to arrest him in Gethsemane, Judas has to identify him with a kiss (Matthew 26:47–56), suggesting Jesus blended in with his disciples. Likewise, when Mary Magdalene encounters the risen Jesus outside the tomb, she mistakes him for a gardener (John 20:16).

From this, it follows that Jesus likely dressed and appeared like other Jewish men of his time. While we may never know exactly what he in detail looked like, we can still make educated guesses based on historical and archaeological evidence, cultural norms of first-century Judea, and early artistic depictions. Surprisingly, these often challenge our modern mental image of Jesus—a long-haired, bearded man in flowing white robes. here is what scientists say about fiction vs. reality.

Art vs. Reality

We should not expect any relic attributed to Jesus, such as for instance the famous Shroud of Turin, to reflect the familiar image we see in Western iconography. There are rather hints into a very different direction.

Over the centuries, many Jesus-relics such as supposed strands of Jesus’ hair were revered. Frederick III of Saxony—Martin Luther’s protector—claimed to possess even a strand from Jesus’ beard among his 19,003 relics. Yet, even he began to doubt their authenticity, ultimately banning relic veneration in Saxony in 1524.

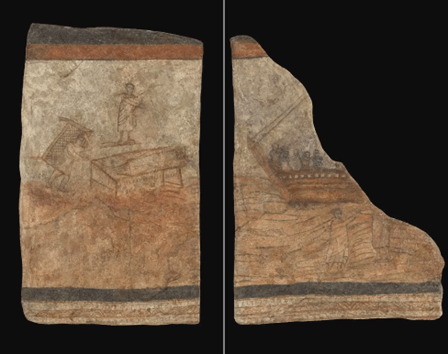

Early Christian art presents Jesus rather as a young man with short, dark hair and no beard at all. Some of the earliest images, dating to around 250 CE, come from the church in the ruins of Dura-Europos on the Euphrates River. And they do not reflect our traditional Jesus image at all.

This doesn’t preclude Jesus occasionally having a beard—forty days in the desert leave little room for shaving. But in general, the Greco-Roman aesthetic favored a clean-shaven, short-haired look. Even philosophers kept their hair cropped. Beards only became fashionable again in the Roman world under Emperor Hadrian (117–138 CE).

Depictions in the catacombs of St. Domitilla in Rome show Jesus hence equally as youthful and beardless, and even by the sixth century, mosaics in Ravenna still portrayed him without a beard.

A recently discovered fresco from the sixth century, found in the ruins of a church in southern Israel, depicts Jesus again with short curly hair and no beard—closer to the appearance of mythological figures like Paris or Ganymede than the long-haired figure of modern imagination.

Beards were not a specifically Jewish trait in antiquity. In fact, Roman authorities often struggled to distinguish Jews from other peoples—an issue referenced in the Book of Maccabees. The Judaea Capta coins, issued after Rome’s conquest of Jerusalem in 70 CE, depict bearded Jewish captives. But this might have been an artistic device to portray Jews as “barbaric (“barba” meaning beard of course).

Jesus may have had a beard—or not—but the evidence leans thus rather toward a clean-shaven or at least closely trimmed look. One thing is almost certain: long hair was not part of his appearance. Men who wore long hair and beards were usually under a Nazirite vow, dedicating themselves to God by abstaining from alcohol and refraining from cutting their hair. Jesus, however, drank wine and was even accused of drinking too much. We all know the miracle performed by turning water into wine and know, what he drank for Last Supper. Had he looked like a Nazirite, his behavior would have been cause for commentary in the Gospels.

Hence, for anyone evaluating relics like the Shroud of Turin, look for a Jesus with short hair and either no beard or a modest one.

And now to clothing: What Did Jesus Wear?

Today’s depictions of Jesus often show him in a long, flowing white robe, resembling a Roman toga. But what did a first-century Jewish man from Galilee really wear?

Two garments venerated as relics—the Holy Tunic of Trier and the Holy Tunic of Argenteuil—are preserved today and reflect the kind of clothing Jesus may have indeed worn.

The Holy Tunic in Trier is venerated as the seamless robe Jesus wore during his crucifixion, over which Roman soldiers cast lots, as described in the Gospel of John. Tradition holds that Helena, the mother of Constantine the Great, brought it to Trier in the fourth century. However, written documentation only appears in the Middle Ages. While material analysis confirms its age, it cannot confirm a first-century origin.

The tunic in Argenteuil, housed in the Basilica of Saint-Denys near Paris, has a similar story. Some say Charlemagne brought it to France, while others attribute it to a Byzantine empress. Radiocarbon testing indicates significant age, but again, no definitive link to Jesus.

Despite doubts about their authenticity, both garments are however at least plausible in style.

In Jesus’ time, upper-class men occasionally wore long robes to display status—similar to modern depictions. But Jesus himself warned against religious elites who “walk around in long robes” seeking honor (Mark 12:38–39). Such sayings are considered historically reliable, suggesting Jesus favored modest clothing.

The typical man in Roman-era Judea wore a knee-length tunic (chiton), often woven from a single piece of wool or linen, with decorative bands (clavi). Over it, he draped a large woolen mantle—called a himation in Greek or pallium in Latin. This rectangular cloth wrapped around the body, leaving one arm free, and provided warmth in layers when necessary.

Jesus is described as wearing such a mantle in Mark 5:27: “When she heard about Jesus, she came up behind him in the crowd and touched his cloak [himation], because she thought, ‘If I just touch his clothes, I will be healed.’”

In colder weather, people might add a cloak, sometimes worn without a tunic beneath it—a style favored by some ascetic philosophers.

Based on the evidence, Jesus likely wore a simple chiton and himation—garments practical for a traveling teacher and consistent with modesty and humility. In terms of form and function, the tunics in Trier and Argenteuil could thus very well resemble what he wore, even if they cannot be directly linked to him.

So what can we conclude?

Jesus, by all reasonable accounts, was a modestly dressed, short-haired and shaved man of his time—radical in word and deed, not in appearance. And that is may be also part of the point: his power came not from what he wore or how he looked, but from what he taught.

Footnotes

- See discussions on Pontius Pilatus, Calpurnia, and Queen Berenice: Ancient sources are limited to brief mentions in Roman and Jewish historical texts.

- Giv‘at ha-Mivtar excavation: Discovery of a crucified man with a nail in his heel (1968), a rare archaeological proof of Roman crucifixion practices.

- Tacitus, Annals (c. 116 CE), Book 15, Chapter 44.

- Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews, Books 18 and 20 (c. 93–94 CE).

Leave a comment