When we think about relics associated with Jesus, garments like the Shroud of Turin come to mind. But some relics go beyond cloth—and straight into the realm of the strange and controversial. Among these is the so-called Holy Foreskin.

Yes, you read that right.

Across medieval Europe, churches in Germany, Italy, and France once claimed to possess one of up to 18 different foreskins of Jesus Christ. The last known example was stolen in 1983 from the Italian town of Calcata, where it had been kept for centuries.¹

The existence of such a relic, however bizarre it may sound today, stems from the historical fact that Jesus was Jewish. According to Jewish tradition, boys are circumcised on the eighth day after birth. The Gospels confirm that Jesus underwent this ritual (Luke 2:21). This naturally raises the question: Could his foreskin have actually been preserved?

And if so, what could we learn from it today—perhaps we could get a DNA profile? (For the genetics fans consider: Would that be XY due to Mary or half Holy Spirit?)

While this may sound like modern speculation, the fascination with Jesus’ physical body, including his being portrayed naked and being circumcised, has deep historical roots, both theologically and artistically.

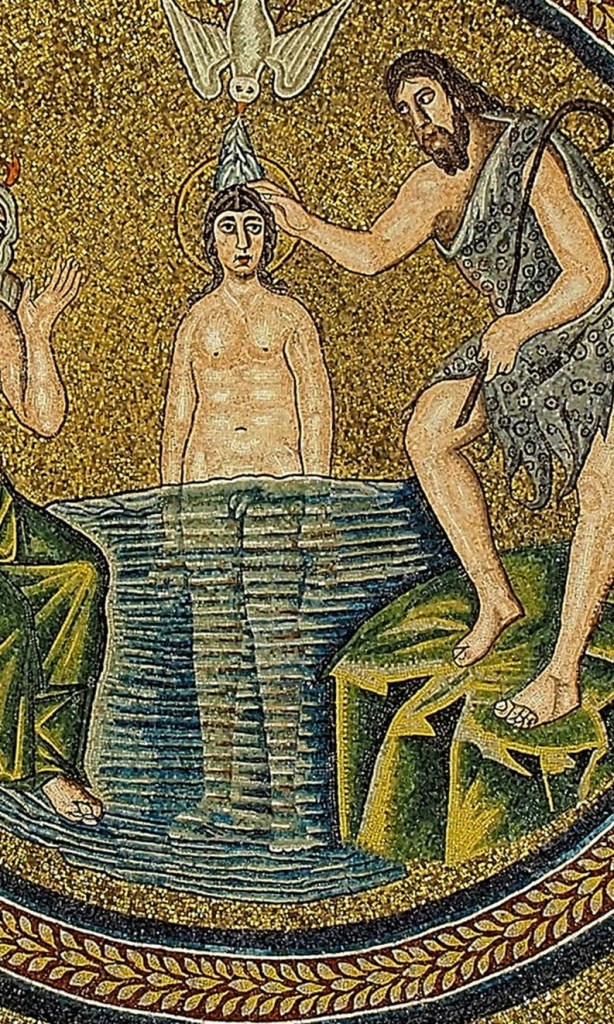

Mosaic of the naked Christ in the Arian Baptistery in Ravenna, central medallion of the dome (6th century).

Photo: Ingola, public domain (CC0)

Nudity of Christ in Christian Art

Early Christian art reflects a surprisingly open attitude toward nudity, at least in sacred contexts. In the 6th-century baptisteries of Ravenna, Jesus is for instance depicted nude during his baptism in the Jordan River—reminiscent of how Roman emperors and gods were portrayed in statues.²

In Greco-Roman culture, nudity was a symbol of beauty, health, and heroism. Daily exercise in the nude was standard practice in Roman bathhouses and gymnasiums. Nudeness wasn’t automatically sexual or shameful—it was visual rhetoric. Would Jesus have been baptized naked? Very likely.

But beyond that, nudity would have been much more complicated for him as a Jewish man in Roman-occupied Judea.

Baptism of the naked Jesus, Arian Baptistery, Ravenna (6th century)

The Problem with Circumcision

In Hellenistic and Roman societies, circumcision was not only unusual—it was viewed with disgust. It was equated with castration or seen as sexually obscene. Circumcised men were mocked, and this stigma affected Jewish communities, including in Galilee where Jesus grew up.

Some Jewish men went thus to great lengths to reverse their circumcision. A surgical procedure called epispasm even attempted to restore the appearance of an intact foreskin by stretching remaining skin. Roman medical writer Celsus, writing during the time of Emperor Tiberius (14–37 CE), described such operations as being performed “for reasons of modesty.”³

The issue was of course not just social—it had deep political and religious consequences. Rich Jewish men going to Roman Thermal Baths in the metropolis would have been looked in disgust at or even be excluded.

As Judea became more integrated into the Greco-Roman world, conflicts emerged between Jewish religious traditions and imperial expectations. The elite Jewish ruling class under Herod was closely aligned with Roman customs, while the broader population often resisted this cultural assimilation.

The issue of circumcision became central during the reign of King Antiochus IV Epiphanes (ca. 215–164 BCE), who banned the practice as part of his campaign to Hellenize Judea. The First Book of Maccabees recounts the brutal persecution of those who defied the decree:

“Women who had their sons circumcised were put to death… with their babies hung around their necks.” (1 Macc 1:60–61)⁴

In response, traditionalist Jewish groups doubled down. By the second century CE, the priah technique extended the circumcision to include internal foreskin tissues, making reversal impossible and ensuring clear religious distinction.

The early Christian church had however soon a practical problem: requiring circumcision would’ve been a major deterrent for Roman and Greek converts. The Apostle Paul thus abolished circumcision as a Christian obligation.⁵

In the apocryphal Gospel of Thomas (30–200 CE), Jesus reportedly responds to the question, “Is circumcision useful?” with: “If it were useful, children would be born circumcised.” (Thomas 53)

By the time of the Roman Emperor Hadrian, circumcision was legally banned, reflecting the empire’s disdain for the ritual.

All of this makes the idea that early Christians—or worse, Romans—would have kept Jesus’ foreskin highly unlikely. Not only would it have been considered blasphemous, it also directly contradicted Jewish law, which requires the foreskin to be buried immediately after the Brit Milah (circumcision ceremony).

Given these facts, we can confidently say that the “Holy Foreskins” circulating in medieval Europe were not authentic. Whether created for money, power, or devotion, they were fabrications. There was certainly also a part voyeurism in this all.

Eventually, the Church had enough. In 1900, Pope Leo XIII forbade all discussion of the Holy Foreskin under threat of excommunication.

Michelangelo’s Christ Bearing the Cross: the original (left) and the version later covered with a bronze loincloth (right). In both, Jesus is depicted uncircumcised—just like Michelangelo’s David.

Over time, our cultural expectations around nudity—especially in sacred spaces—have changed. In churches today, modesty is the rule. Even masterpieces like Michelangelo’s sculptures were later altered to conform to newer standards of decency.

So, did go Jesus naked? Sometimes in private, perhaps—especially at the Jordan. Otherwise he would have covered himself. Was his foreskin preserved? Almost certainly not.

But the enduring fascination with the physicality of Christ tells us something above all: that people have long sought tangible, even bodily, connections to the divine. Sometimes, the search for relics reveals more about us than about the past.

Footnotes:

- The relic of Calcata was stolen in 1983 and has not been recovered.

- Early Christian mosaics in Ravenna are among the few surviving artworks showing a nude Christ.

- Celsus, De Medicina, Book VII – on epispasm surgeries.

- 1 Maccabees 1:51–64 (EU translation).

- See Galatians 5:6, Romans 2:28–29.

Leave a comment