In human history, it is rather unusual for significant changes to be driven not by warfare but by enthusiasm. A notable exception to this is the discovery made by the Italian farmer Ambrogio Nocerino, [i] who, while digging a well in his garden in the sleepy coastal town of Resina[ii] at the foot of Mount Vesuvius near Naples, came across worked marble—at a depth of about 20 meters, within the hard tuff rock. This discovery not only captured local attention but ultimately sparked widespread excitement across Europe when it was revealed that the marble came from the theater of the Roman city of Herculaneum (Fig. 2).

As rare as the outcomes of this European-wide enthusiasm[iii] is the fact that scientific articles begin with an emotional uplift. However, our intention here is to focus precisely on this emotional dimension, which is too often overlooked in the scientific study of archaeological finds, and particularly in their presentation within museums.

What the farmer Nocerino unearthed after consulting with Emmanuel Maurice of Lorraine, the Duke of Elbeuf, [iv] who was building a villa nearby (Fig. 3), is now part of the Dresden Sculpture Collection. On one wall, the three over-life-size marble statues are displayed. They are usually referred to as “Herculanean Women,” [v] but the information provided about them in the exhibit does not go beyond this simple detail.

Yet these statues (Fig. 1) truly merit in-depth contextualization due to their extraordinary significance not only for the development of modern archaeology but also for the history of humankind.

Their discovery and subsequent presentation can offer valuable insights not only into ancient craftsmanship or the value of – admittedly high-quality – worked marble but also into the early stages of archaeology as a scientific discipline. Beginning with these finds, archaeology heralded a new era of scientific thinking and systematic research.

It was the sensational enthusiasm over the discovery in the dark depths, the tragic history of the city’s destruction, and the wise decisions of Charles III of Bourbon and his wife Maria Amalia of Saxony that laid the foundation for archaeology as a science. Let us delve deeper into this.

The Circumstances of the Discovery

While Pompeii is today more widely known due to its extensive excavation, the majority of Herculaneum remains deeply buried beneath the solid tuff. Less than a quarter of the ancient city has been uncovered so far. Rich villas, complete temples, and ancient libraries[vi] still lie[vii] hidden underground, effectively preserved as a petrified snapshot of life in ancient Rome.

The differences in the nature of the burial of the two cities are the cause for the limited excavation: while Pompeii was primarily buried under a dense layer of ash, Herculaneum was engulfed by multiple intense pyroclastic flows. These extremely hot, fast-moving avalanches buried the city under tons of lava, mud and ash. Due to the collapse of the ground after the eruption, the earth beneath Herculaneum sank in addition by about four meters, and the sea was pushed about 400 meters back from the ancient shore due to the rising seabed caused by the stream of lava.

Nonetheless, the history of modern archaeology is inextricably linked to the discovery of the far less accessible Herculaneum—an event that took place in 1709, long before the excavation of Pompeii.

The discovery made during the digging of a well triggered a remarkable series of events that would revolutionize the scientific and cultural perception of antiquity. As previously mentioned, the discoverer, the farmer Ambrogio Nocerino, sold the first marble found to Emmanuel Maurice of Lorraine, the Duke of Elbeuf, who was building a villa nearby, which still stands as a ruin today. Motivated by this initial find, the duke ordered further excavations at great depth within the tuff, leading to the creation of tunnels and the eventual recovery of three over-life-size marble statues.

The discovery of these “Herculanean Women”—three female statues that would later play a central role in art-historical debates—marked the beginning of a new era in the study of antiquity, despite the initially treasure-hunting approach. The duke hastily had the statues removed, wrapped in cloths, and sent as a gift to Eugen of Savoy, to settle financial obligations. They were enthusiastically received by him. The statues were placed in the Sala terrena of the lower Belvedere in Vienna[viii] and later acquired by Augustus the Strong, the Elector of Saxony, for his collections. [ix]

The Exhibition and Excavations

The exhibition of the statues caused a stir, and after the renewed Spanish conquest of Naples (which had been temporarily held by Austria), the new Neapolitan king, Charles III of Bourbon, and his wife Maria Amalia of Saxony, the granddaughter of Augustus the Strong, ordered systematic excavations. Initially, under the Spanish Roque Joaquín de Alcubierre, [x] the focus was merely on the retrieval of artworks. Even today, one can still see the holes in the walls of Herculaneum’s buildings, where workers under harsh conditions, in cold and darkness, had hacked frescoes from the walls. The idea that these walls could ever see the light of day again was deemed too far-fetched.

However, the Swiss Karl Weber soon took over the excavations and began making the first archaeological records. An impressively accurate map of the Villa of the Papyri, created by him, has survived to this day.

The account of these excavations is largely forgotten, yet they represent a breathtaking chapter in the history of the submerged city. They took place 20 to 30 meters beneath the surface, and during their duration, volcanic eruptions occurred repeatedly. Toxic gases filled the tunnels and rose through the excavation shafts into the houses above, leading to fatalities. In the depths, there were explosions of the mine gases, flooding, blindness, and scurvy. [xi] Weber himself ultimately died as a result of the conditions during the subterranean search.

The lack of records from Alcubierre’s excavations, the presence of ancient Roman retrieval tunnels, [xii] and the fact that the local population also engaged in treasure hunting made the search in the depths a high-stakes gamble. One passage would be filled in to dig another, and its existence would be forgotten. Tunnels thus frequently collapsed.

Despite Life-Threatening Conditions: The Continued Excavations

Despite the life-threatening and today unimaginable conditions underground, the work at Herculaneum continued with haste. All of Europe envied the King of Naples for his treasure, which he guarded zealously not only against intruders but also against foreign scholars, such as the legendary Johann Joachim Winckelmann.

The excavations uncovered not only magnificent wall paintings but also everyday objects of inestimable value. Of particular interest was the so-called Villa of the Papyri (Figs. 4, 5, 6), which contained an impressive collection of ancient texts. This find remains the most significant discovery of an ancient library to date.

The subterranean tunnels of Herculaneum eventually became a site of pilgrimage, with large sums paid to treasure hunters and forgers for a share of the coveted artifacts. Even the site’s curator engaged in selling counterfeit frescoes and likely original objects as well. To this day, the French National Library holds a Greek statuette of a cow originating from Herculaneum.

Mismanagement and Scandal Surrounding the Finds

The treatment of the artifacts, particularly in the early phases, was so poor that it led to numerous scandals. Letters of indignation from Winckelmann[xiii] survive. While his sharp criticisms may have been partly motivated by personal grievances, they were well-founded and reflect a judgment far ahead of his time. For instance, he denounced the melting down of fragments of bronze horses from a quadriga found in Herculaneum’s theater to cast a statue of the reigning king, as well as the practice of cutting wall paintings from ancient structures (Figs. 7, 8) to frame and transport them.

Winckelmann’s criticisms culminated in his seminal scientific reports, published as open letters in 1762[xiv] and 1764, [xv] which were among the first systematic analyses of the excavation’s methods and their flaws.

It was through these excavations, and the critiques they provoked, that archaeology as a scientific discipline was born.

The Herculanean Women

Returning to the statues in Dresden, the “Herculanean Women” were not only the first significant archaeological find of modern times, but also inspired Johann Joachim Winckelmann’s groundbreaking study Reflections on the Imitation of Greek Works in Painting and Sculpture. In this 1755 treatise, Winckelmann devoted several pages to these statues, which he identified as depictions of Vestal Virgins, calling them “the first great discoveries of Herculaneum.” With these words, he placed the statues in a context that emphasized not only their aesthetic significance but also their profound influence on the development of art history and archaeology.

This was already a monumental achievement, yet today we must view these artifacts in an even broader light.

The earlier—and unfortunately still prevalent—practice in many museums of categorizing artifacts by criteria such as size, age, or monetary value must be reevaluated. Instead, these finds should be reconsidered within their original context, specifically the theater of Herculaneum. Failing to do so disregards the multilayered historical, emotional, cultural, and scientific significance of such objects.

Herculaneum offers a striking testament to the interplay of natural disaster and history. The discoveries from this ancient city were not only foundational for the evolution of archaeology but also contributed significantly to our understanding of the Roman world and the development of volcanology. Herculaneum was home to the first center for volcanic research, underscoring the scientific importance of the submersion history of these finds.

At the same time, these artifacts evoke the awe and horror that archaeological discoveries can inspire. They vividly illustrate how material culture from past civilizations resonates deeply with human emotions.

The tragedy that befell Herculaneum during the catastrophic eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 CE highlights the destructive power of nature. Within just 19 hours, the city was completely buried by pyroclastic flows and mudslides. Scorching waves obliterated buildings, tore roofs off structures, and hurled them into the sea. They shattered walls and killed the inhabitants in the most harrowing ways imaginable. The historical and emotional dimensions of this event are as compelling as the scientific insights it has yielded.

This tragedy also serves as a somber parallel to the present. The magma chamber of Mount Vesuvius, which destroyed Herculaneum, remains active. In 2023 and 2024, significant and sustained seismic activity in the Phlegraean Fields and the areas around Naples and Pozzuoli caused repeated earthquakes that unsettled millions of residents. The ground in the region has visibly risen since, underscoring the ongoing volcanic threat and the pressing need for research and disaster preparedness.

The Exhibition: A Call for Contextualization

Reducing the Herculanean women to mere works of art fails to do justice to their historical, cultural, and human significance. This perspective, when viewed in light of the catastrophic event that buried them, can even be considered inhumane.

These statues, preserved by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 CE, are not only masterpieces of ancient craftsmanship but also witnesses to a devastating tragedy that wiped out an entire community. Viewing them solely as artistic objects disregards the human dimension of their context. The Herculanean women come from a city whose population perished under dramatic circumstances. These artifacts embody the societal, religious, and cultural values of a vanished world and should not be trivialized through a purely aesthetic lens.

Fig. 9: Impression of the face of the statue of Nunius Balbus, which was recovered from the depths of the Herculaneum theater. The striking impression is located on the ceiling of the excavated part of the theater.

From a modern perspective, such an isolated interpretation is deeply problematic, as it undermines the ethical responsibilities of both science and museology.

Artifacts like the Herculanean women demand holistic contextualization, recognizing their artistic, historical, and human dimensions. This approach aligns with the goals of contemporary archaeology and museology, which aim to present the past in all its complexity and with due respect. Ignoring the human suffering tied to Herculaneum’s destruction is not only historically irresponsible but also fosters an alienation that contradicts the primary purpose of preserving and exhibiting such artifacts: to promote understanding and empathy for past cultures and their people.

The statues of the Herculanean women, currently housed in the Sculpture Collection at the Zwinger in Dresden, deserve an exhibition that contextualizes them within the events of ancient Herculaneum and the development of archaeology as a discipline.

Toward a Holistic Presentation of the Herculanean women

A thorough exhibition of the Herculanean women should naturally begin by illustrating the methods of early treasure hunting and the gradual transition to modern archaeology—developments that are deeply intertwined with the exploration of Herculaneum.

Equally important is an introduction to the history of the city itself, including its destruction and preservation by pyroclastic flows. This narrative should encompass the circumstances under which the statues were buried, as well as their discovery, excavation, and eventual journey to Dresden. Such contextualization should precede any detailed analysis of the works themselves. Only after establishing this historical and archaeological framework can their function, artistic techniques, and significance in ancient society be meaningfully explored—topics that currently dominate their interpretation.

Reimagining the Exhibition Context

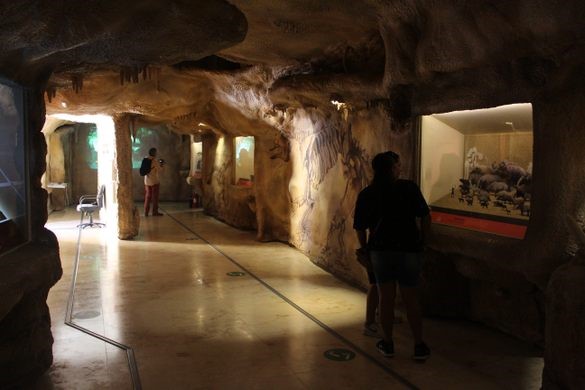

The presentation of the statues in a setting that evokes their original environment—specifically, the subterranean, sunken theater of Herculaneum—is an essential consideration. Incorporating contemporary drawings and reports from the time of their discovery would provide valuable additional context.

This approach would not only enhance the understanding of the artifacts’ historical and cultural dimensions but also create a more immersive and respectful narrative that aligns with modern archaeological and museological standards.

Middle: The archaeological museum of Fuerte El Alto, Campeche, Mexico, a museum recognized by UNESCO as a “Best Practice,” replicates the cave where the displayed artifacts were found. Left & Right: The exhibitions “Egypt’s Sunken Treasures” and “Osiris” by Franck Goddio used light, images, and backgrounds to recreate the excavation context. Neithsabes, CC BY 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Christine Voigtmann, Ulrike Ortrere

Bergmann, Bettina: „The Art of Ancient Spectacle: Herculaneum’s Theater District.“ In: The Art Bulletin, Band 85, Nr. 3, 2003, S. 464–491.

Berry, Joanne: The Complete Pompeii and Herculaneum. Thames & Hudson, London, 2007.

Brion, Marcel: Pompeji und Herculaneum. Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag, Reinbek, 1981.

Daehner, Jens (Hrsg.): The Herculaneum women: history, context, identities. J. Paul Getty Museum, Malibu 2007, ISBN 978-0-89236-882-2.

Daehner, Jens, Knoll, Kordelia, Vorster, Christiane, Woelk, Moritz: Die Herkulanerinnen – Geschichte und Kontext antiker Frauenbilder. Hirmer, München 2008, ISBN 978-3-7774-3985-3.

Deiss, Joseph Jay: Herculaneum: Italy’s Buried Treasure. J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, 1989.

Lazer, Estelle: „Preservation and Presentation of Herculaneum’s Archaeological Legacy.“ In: Conservation and Management of Archaeological Sites, Band 5, Nr. 3, 2002, S. 159–178.

Mattusch, Carol C.: „Rediscovering Herculaneum’s Villa of the Papyri.“ In: The Villa of the Papyri at Herculaneum: Life and Afterlife of a Sculpture Collection, Getty Publications, Los Angeles, 2005.

Muth, Stefan: Archäologie der Katastrophen: Herculaneum und der Vesuv. Böhlau Verlag, Köln, 2008.

Parslow, Christopher Charles: Rediscovering Antiquity: Karl Weber and the Excavation of Herculaneum, Pompeii and Stabiae, 2011.

UNESCO: Herculaneum Conservation Project Reports. Diverse Berichte, 2001–heute.

Wallace-Hadrill, Andrew: Herculaneum: Past and Future. Frances Lincoln, London, 2011.

Winckelmann, Johann Joachim: Gedanken über die Nachahmung der griechischen Werke in der Malerei und Bildhauerkunst. Dresden, 1755.

Zanker, Paul: Pompeji: Stadtbild und Wohngeschmack. Verlag C.H. Beck, München, 1995.

Endnotes

[i] In 1709, a farmer named Ambrogio Nocerino, known locally as Enzechetta, uncovered fragments of marble while expanding a well to irrigate his garden near the Church of San Giacomo and the Alcantarine Brothers’ forest. A craftsman working for the Duke of Elboeuf noticed these pieces and purchased some to adorn chapels in various Neapolitan churches. When the Duke learned of this discovery, he acquired the well and conducted an initial, rudimentary investigation of the finds between 1709 and 1711 by commissioning the excavation of subterranean tunnels. The unearthed artifacts were stored in the nearby Villa d’Elboeuf.

It was later revealed that the well-digging project had breached the scenae frons (stage wall) of the theater of Herculaneum, initially misidentified as a Temple of Hercules. However, it soon became evident that the ruins were part of the ancient city destroyed by the catastrophic eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 CE.

Excavations, which included the stage wall, the stage house, and part of the theater’s seating areas, yielded a wealth of artifacts. These included marble columns of African, alabaster, and yellow marble; an architrave inscribed with praise for a consul from 38 BCE (Claudius Pulcher); terracotta dolia; and nine statues—eight female figures and one male statue in a heroic nude pose, some still located in their original niches. Among these discoveries, three statues, later known as the “Herculanean Women,” were sent to Vienna, while others were eventually transported to the royal residence in Portici.

The excavations were halted at the behest of local authorities, who expressed concerns about potential damage to the overlying structures. Nevertheless, the initial discoveries, despite their abrupt cessation, were foundational in uncovering the remnants of Herculaneum and laid the groundwork for more systematic archaeological endeavors in the centuries to follow.Top of Form

Bottom of Form

[ii] The town of Resina, later renamed Ercolano, has long been associated with the ancient city buried beneath it. Johann Joachim Winckelmann proposed that Resina might correspond to “Rectina,” a location mentioned by Pliny the Younger in his first letter to Tacitus. This name, frequently misunderstood as referring to a woman, is now considered by some scholars to denote a place rather than a person.

While this interpretation has been contested in certain circles, we find the connection plausible and compelling. The linguistic and historical context supports the view that Resina, with its proximity to Herculaneum, aligns with Pliny’s account, further enriching our understanding of the geography and historical narratives surrounding the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 CE.

[iii] The book Le Antichità di Ercolano Esposte (The Antiquities of Herculaneum Displayed) is an eight-volume work featuring copperplate engravings of artifacts uncovered during the excavations of the ruins of Herculaneum in what was then the Kingdom of Naples (modern-day Italy). Published between 1757 and 1792, copies of the work were distributed to select recipients across Europe.

Despite its title, the book showcases objects from all the excavations undertaken by the Bourbons around the Gulf of Naples, including Pompeii, Stabiae, and two sites in Herculaneum: the then-called Resina (now Ercolano) and Portici. The publication significantly influenced the Neoclassical movement in Europe by providing artists and decorators with access to a rich repository of Hellenistic motifs.

[iv] For details on the circumstances surrounding the discovery, see the excellent book by Christopher Charles Parslow, Rediscovering Antiquity: Karl Weber and the Excavation of Herculaneum, Pompeii, and Stabiae (2011).

[v] The Large and The Small Herculaneum Woman, Universita Ca’ Foscari, Venezia, Doctoral Thesis 2014–2015, Angeliki Ntontou

[vi]A scientific conference in Herculaneum addressed the question of whether the Villa of the Papyri might conceal an additional, significantly larger library. The papyri discovered thus far in the villa represent a specialized collection belonging to a follower of Epicurus. However, it is indeed plausible to hypothesize that this likely imperial villa housed a more comprehensive library. To date, only the upper floor and a portion of the facade have been explored, and even these primarily through tunnels. This limited exploration is due to the extreme instability of the building, which was fractured by the impact of the lava wave.

[vii] During a recent excavation in the Villa of the Papyri, a chest full of textiles was discovered. However, due to the looming conservation costs, it was reburied in the damp tuff.

[viii] In his influential work Gedanken über die Nachahmung der griechischen Werke in der Malerei und Bildhauer-Kunst (1755, 2nd edition 1756), Winkelmann described the staging of the ancient statues in the Viennese palace commissioned by Prince Eugene as follows: “This great connoisseur of the arts, in order to have a distinguished place where they could be displayed, had a Sala terrena built specifically for these three figures, where they, along with some other statues, were placed.”

[ix] The Elector of Saxony, Friedrich Augustus II, acquired the three Herculaneum statues for his collection of antiquities from the estate of Eugene of Savoy in 1736/37. They are now part of the Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden. The transfer from Vienna to Dresden was described by Winckelmann: “The entire academy and all the artists in Vienna were practically in an uproar, as there was only vague talk of the sale, and everyone watched with sorrowful eyes as they were taken from Vienna to Dresden.”

Johann Joachim Winckelmann: Gedanken über die Nachahmung der griechischen Werke in der Malerey und Bildhauerkunst. Waltherian Publishing, Dresden and Leipzig 1756.

[x] Roque Joaquín de Alcubierre was born on August 16, 1702, in Zaragoza. He studied in his hometown before joining the army’s engineering corps as a volunteer, serving in Girona, Barcelona, Madrid, and other Spanish cities. While working on the construction of the new palace of King Charles III of Naples in Portici, he became aware of the excavations initiated by Elbeuf. In 1738, he received permission from the king to conduct further excavations. During these, he discovered a statue of Hercules and the ancient theater previously uncovered by Elbeuf. As the excavations progressed, over 200 frescoes and statues were found, many of which are now housed in the National Museum of Naples. Later, the Swiss archaeologist Karl Weber took over the excavations and began to approach the work in a much more organized manner. Alcubierre was also involved in the excavations of Pompeii and Stabiae. He died on March 14, 1780, in Naples.

[xi] See Parslow, Christopher Charles: Rediscovering Antiquity: Karl Weber and the Excavation of Herculaneum, Pompeii and Stabiae, 2011.

[xii] Emperor Titus, as reported by Suetonius, established a commission for the recovery of artifacts after the eruption of Mount Vesuvius. It is suspected that some of the statues in the Baths of Caracalla in Rome originated from Herculaneum. An inscription reading “ex abditis locis” (from hidden places) points to this possibility.

[xiii] Johann Joachim Winckelmann, Sendschreiben von den Herculanischen Entdeckungen. Herculanische Schriften I, hrsg. von Stephanie-Gerrit Bruer, Max Kunze (Mainz 1997); Nachrichten: Johann Joachim Winckelmann, Nachrichten von den Herculanischen Entdeckungen. Herculanische Schriften II, hrsg. von Stephanie-Gerrit Bruer, Max Kunze (Mainz 1997)

Johann Joachim Winckelmann, the founder of classical archaeology, lived in Rome from 1755 onward. Early in his stay, he visited villas, palaces, and collections of ancient artworks to study them and gather material for his most influential work, The History of Art in Antiquity (Dresden, 1764). Between 1758 and 1767, Winckelmann traveled to Naples four times, which was then part of the Spanish Bourbon Empire, as well as to the ancient sites of Herculaneum and Pompeii, where excavations had started in 1738 and 1748, respectively. The artifacts discovered in these excavations were stored in the royal summer palace in Portici. Winckelmann was able to see these collections, which was a privilege granted to only a few. However, he had to gain access secretly, often with the help of friends or through bribery. This was not only due to his position with the Pope but also because his sharp comments on the excavation methods and previous publications had caused displeasure among the authorities.

Winckelmann published his observations in the popular form of detailed letters, including those to Count Brühl in Dresden and J.H. Fuseli in Zurich. These writings made the excavations and finds known to a broader public in Northern Europe and had a profound impact: they sparked a wave of enthusiasm that permeated all areas of life. Women wore clothes in the ancient style, furniture and dishes in the Pompeian style became fashionable, and Pompeian wall paintings gained popularity. Thanks to the beginning of mass production, such as the invention of wallpaper, these signs of culture and education became affordable for bourgeois households as well.

In German, these works were published by St.-G. Bruer and M. Kunze in volumes 2.1 and 2.2 (1997) of the annotated complete edition of Winckelmann’s works: Johann Joachim Winckelmann, Schriften und Nachlass. Part 3 of these “Herculanean Writings,” edited by A.H. Borbein and M. Kunze (2001), contains letters, drafts, and reviews of the Herculanean writings, allowing readers to trace Winckelmann’s working process and contemporary reactions.

[xiv] He already addresses the ancient sites in a scholarly manner, discussing their destruction and rediscovery, and then proceeds to examine the findings.

[xv] It was officially dedicated to the Swiss historian and politician Johann Heinrich Fuessli, but intended for the public. Fuessli was a personal friend of Winckelmann, who had accompanied him on his third trip to Herculaneum. The letter builds upon the previous one and delves deeper into many discoveries that were only briefly addressed in the earlier work. The theater of Herculaneum and its architectural structure are discussed in detail, as well as ancient texts on theater, stage, and drama production. Winckelmann also describes the main gate of Pompeii, tomb monuments outside the city, and several residential houses with wall paintings. Additionally, he includes detailed discussions on statues and portraits that had already been mentioned in the letter but were not included in his major work, History of the Art of Antiquity (Dresden, 1764).

Leave a comment