Until today, there is a debate about the date of the eruption of Vesuvius in 79.

The eruption was long believed to have occurred on August 24th based on the eyewitness account of Pliny the Younger, who observed the eruption from a distance. However, historians and scholars have debated whether the day he gave for the eruption is accurate.

Very early on, scientists suggested that the eruption may have occurred in October or even November, based on evidence from archaeological excavations and the discovery of certain fruits and organic materials that would not have been in season in August.

It must be noted that Pliny the Younger wrote his account of the eruption of Mount Vesuvius around 30 years after the event occurred, in late 107 or early 108. He was not present at the eruption site, but instead witnessed the event from a distance while staying at his uncle’s house, Pliny the Elder, in Misenum. Pliny the Elder was the admiral of the Roman fleet at the time and sailed closer to Vesuvius to investigate the eruption, while the younger watched from afar.

Therefore, while Pliny the Younger’s written account of the eruption is considered one of the most important historical records of the event, he wrote it many years after the fact. He was 18 when the eruption happened, and 48 when he wrote his letter. It may thus be asked how accurate his memory was.

Moreover, there is doubt about the content of the letter itself.

Pliny the Younger’s letter

Until today the letter from Pliny the Younger to Tacitus remains the best known and most commonly accepted historical source for the date of the Vesuvius eruption. Let us take a closer look at what it says:

According to its best known copy, the Codex Laurentianus Mediceus, it reads:

“Nonum kal. septembres hora fere septima mater mea indicat ei apparere nubem inusitata et magnitudine et specie.”

“On the ninth day before the kalends of September, around the seventh hour, my mother showed him a cloud unusual both in shape and size.”

(Gaius Plinius Caecilius Saecundus, Epistularum liber VI, 16, C. Plinius Tacitus Suo S.)

The majority opinion is that Pliny the Younger’s letter states that the volcano erupted on nonum kal. septembres, which translates to nine days before the Kalends of September, corresponding to August 24. The ancient Romans counted inclusively, meaning they included both the start and end of a sequence. Using this calculation, August 24 plus August 25 through September 1 equals nine days.

In his letter, Pliny the Younger also describes how the day was hot and how his uncle, Pliny the Elder, took a bath and was barefooted when he learned of the eruption.

For centuries this information was considered reliable. Indeed, it was the only one which existed. The letter and a second one in which Pliny the Younger describes his own survival of the volcano eruption, are the only there are and even these only survive in four shamefully badly copied versions. Other sources mention the event, like Suetonius, but they don’t mention an exact date. Only Cassius Dione (Dio (1925). Roman History, Book LXVI, section 21. Penelope.) comes close to giving one: He writes: “at the very end of the summer” (what can be interpreted as meaning August as well as September).

Archaeologists began soon to doubt the dating.

Let us see, who is right, Pliny or the archaeologists. And also if there could be an explanation fitting both.

The indices of the wine

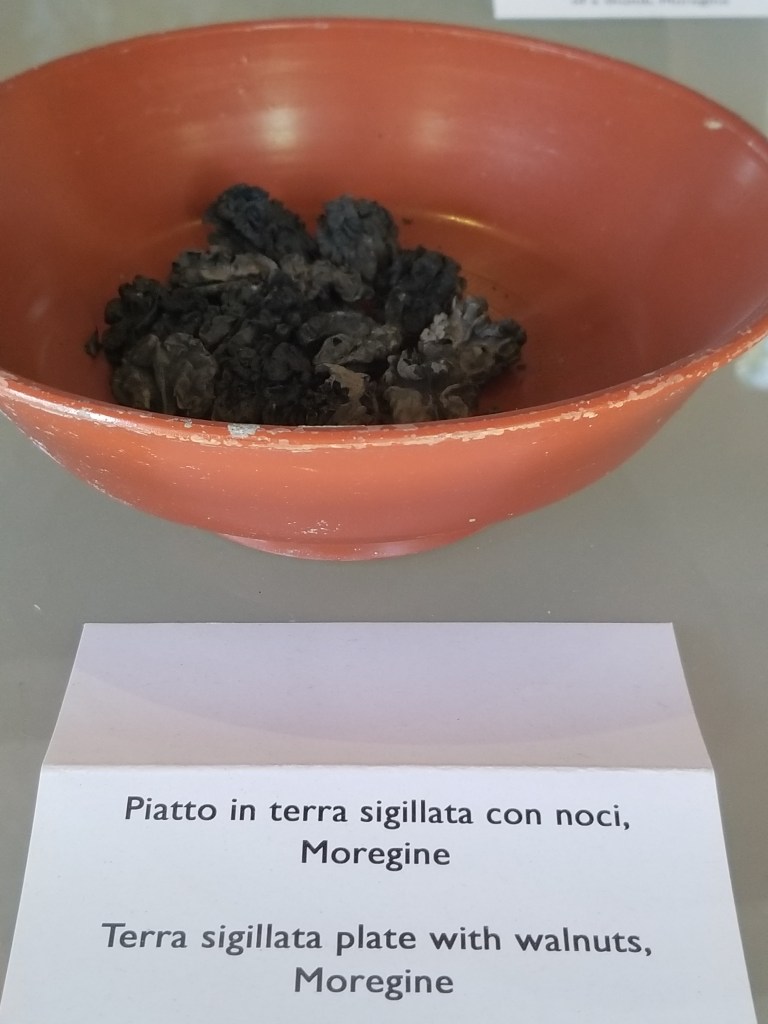

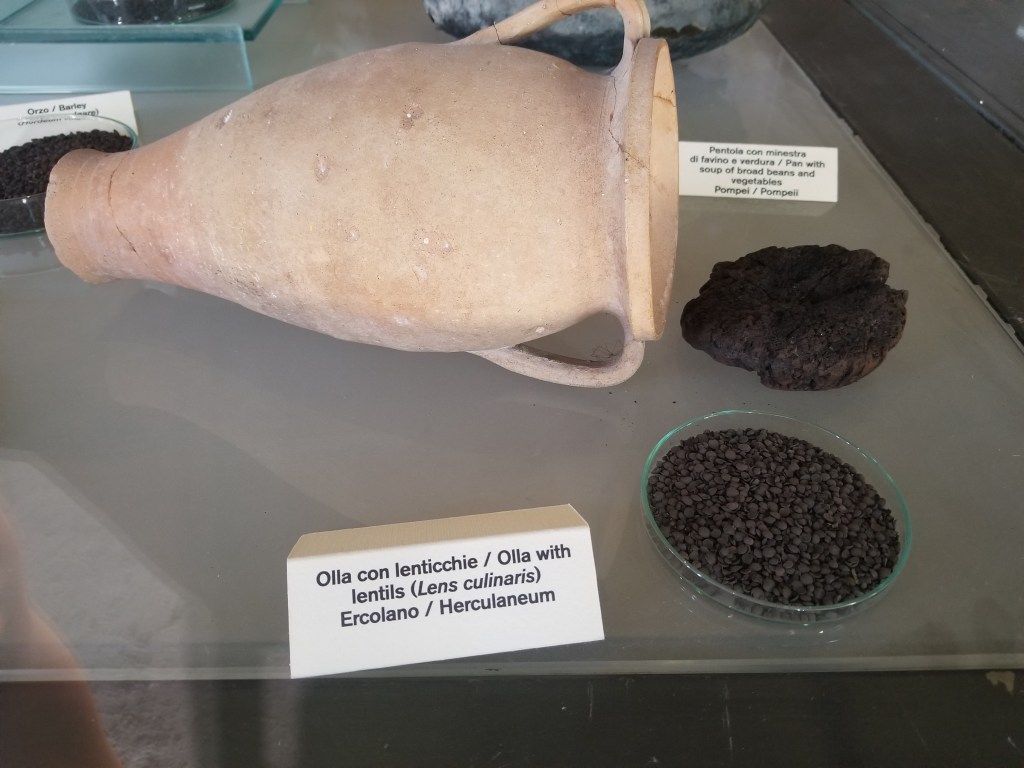

In the excavation of the Vesuvian area, which was sealed by ash and mud, numerous agricultural remains were found. Scholars also found dried fruit, such as figs, dates, and plums. Moreover, they discovered typically autumnal fruit, such as pomegranates in Oplontis, chestnuts, grapes, and walnuts.

There were also signs of the completion of the hemp harvest for sowing, which was usually carried out in September. Moreover, there were indications of the completion of the grape harvest, which was carried out in September or October. Most of the fresh grape juice had been sealed in amphorae, the dolea or dogli, round-shaped vessels in which the Romans stored liquids such as oil and wine, and which were found at Villa Regina in Boscoreale.

These amphorae were only closed after a period of fermentation in the open air lasting about ten days, and the eruption must have occurred after the grape harvest.

An explanation might have been an early harvest, as the Roman Empire coincided with a 500-year warm period, from AD 1 to AD 500. This period caused the warmest period of the last 2,000 years called the Roman Climatic Optimum.

Pliny wrote that the beech, which had previously only grown to the height of Rome, pushed its habitat to the north of Italy. This hot period also favored the spread of viticulture by the Romans in most of Europe. That means that the harvesting time could have been earlier than September close to Naples in the year 79.

In ancient Rome, the Vinalia Rustica festivities took place on August 19th and served to propitiate good weather during the ripening of the grapes. The official start to the harvest was then given by the festivity called Auspicatio Vindemiae. The period of the festivity varied every year in relation to the ripening of the grapes.

In the monthly calendar of works written by Columella, he mentions that grape harvest started in August in lands with remarkably hot climates, such as southern Spain and North Africa. At the beginning of September, the harvest began in Italy in places near the sea and warm ones in general. One can thus conclude that the earliest date for harvest near Naples could have been the last week of August, but a date in September or even October would have been much more likely.

A fresco showing fruit and a freshly baked bread.

The heating and the clothing

In addition to what was mentioned above, typical autumnal objects have been found in houses that were abandoned while in use, such as braziers in the House of Menander. It seems unlikely that a night during a volcanic eruption could have been cold, but maybe there is an explanation. The braziers could have also served for cooking, and the heavy clothing could have been worn to protect against the falling hot ashes. Pliny the Younger’s letter even speaks of people, including his famous uncle, strapping cushions on their heads to protect themselves.

The Text Variations

Analysing the various manuscripts of the Plinian text that have been preserved, it must be said that in truth there are as many versions as surviving copies. This is, what they say:

- Nonum kal. septembres (nine days from the kalends of September, i.e., the 24th of August) (Codex Laurentianus Mediceus)

- Kal. novembres (on the kalends of November, i.e., 1 November) (edition printed in 1474)

- III kal. novembres (three days from the kalends of November, i.e., 30 October)

- Non. kal. … (nine days from the kalends, gives no month) (15th-century version in Paris)

The presence of these variants points to transcription errors that the text has undergone due to the copyists. Indeed, the original letter text of Pliny does not survive. The mostly used Papyrus was not durable and was prone to damage from moisture and insects. As a result, many ancient texts written on papyrus have not survived to the present day in their original form.

Not even the oldest variant of Pliny the Younger’s text is immune to errors. The Roman writing in majuscules without signs and spaces and full of abbreviations did not certainly help in this regard. It is also telling that all 4 copies are uncertain about the same passages. A smudge or damage to the papyrus would have given all of the copyists difficulties. Thus, the date of 24 August, derived from one of the variants of Pliny’s text, is far from certain and may not have been given by Pliny himself at all.

Maybe the eruption just happened on a warm day in September. Or October. Or November…

The indice of the coin

A a numismatic find might indicate that the summer date is false altogether. Indeed, a silver denarius found on 7 June 1974 in the excavation at Pompeii, under the House of the Golden Bracelet (Insula Occidentalis) bears the inscription: “IMP TITVS CAES VESPASIAN AVG P M TR P VIIII IMP XV COS VII PP” – “Emperor Titus Caesar Vespasian Augustus Pontifex Maximus, ninth time with the potestà tribunicia, emperor for the fifteenth, consul for the seventh time, father of the fatherland.”

The discovery of the Pompeian denarius with the indication of the 15th acclamation might allow us to state that the eruption occurred after the issue of this coin, thus in the year in which Emperor Titus held the 7th consulship (79), after the assumption for the 9th time of the potestà tribunicia, i.e., after 1 July and after the 15th acclamation as emperor, allowing us to move the terminus post quem beyond July.

Two inscriptions preserved in Seville and the British Museum in London, dated 7 September and 8 September 79, may make it possible to determine the date of the acclamation. In both inscriptions, one a letter carved in a bronze epigraph by Titus to the decurions of the city of Munigua (today Villanueva del Rio), and the other a discharge diploma found in Fayyum, the 14th acclamation is given together with the dates of 7 September (for Titus’ letter) and 8 September (for the diploma), allowing us to state that the 15th imperial acclamation certainly took place after these two dates.

The terminus post quem of 7-8 September might indicate that the eruption of Vesuvius took place after 8 September.

However, it is still possible that the coin was struck earlier, and the diploma and letter mentioning the 14th acclamation might have been dated long after the event, given that the objects had still to be transported to Spain and Fayyum. Therefore, the coin alone is not 100% certain evidence.

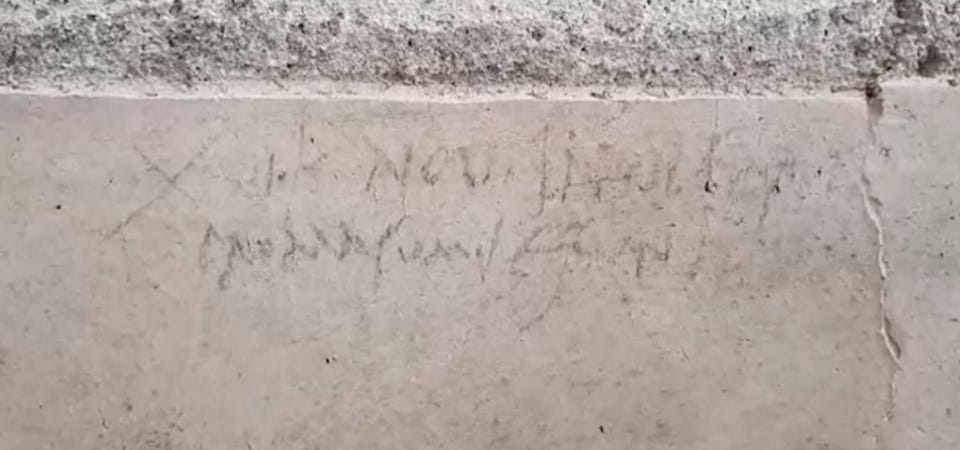

Inscriptions

Other evidence supporting the thesis that the eruption occurred in the autumn can be found in an inscription discovered in 2018 in a house that was probably under renovation during the eruption. The inscription, written in charcoal, bears the date 17 October, but does not include the year, which is usual for wall inscriptions relating to daily life in Pompeii. It most likely refers to the year 79, since charcoal inscriptions are easily erased.

However, the date of the charcoal inscription may not necessarily refer to AD 79. It may have been written earlier and been preserved because it was out of reach of people and weather. Charcoal inscriptions can resist even for decades if left intact, as demonstrated by the charcoal inscriptions still legible on the vaults of the tombs of Porta Nocera. So the inscription is not yet conclusive evidence, but a hint that should be considered in relation to the other evidence, such as the harvested wine, the coin, and the fruits.

The text following the date is an ambiguous reading, but as it is rather amusing, it shall be shared: “XVI (ante) K(alendas) Nov(embres) in[d]ulsit / pro masumis esurit[ioni]” – “On 17 October, he indulged in immoderate eating.”

After considering all of the above evidence, it is much more likely that the eruption of Mount Vesuvius occurred later than August. And perhaps Pliny the Younger wrote just that… but that is just a judgment based on indices. We are still searching for the definitive evidence.

Leave a comment