Ludwig Bechstein was a German writer, well-known for his collection of tales in the German Saga Book. It was first published in 1853 and contains over 500 German folk tales, legends, and sagas that Bechstein collected from various sources. Many of them have a verifiable background.

Two of the most well-known tales in the collection are “The Pied Piper of Hamelin” and “The Lorelei”. However, one of his tales is particularly peculiar: the story of the royal meeting’s fall into the cesspool.

The ancient saga

Bechtstein writes the following:

In days of yore, there resided a count by the name of Heinrich the Seventh in Schwarzburg, who was known to utter a foul saying when he aspired to something lofty, exclaiming: “If I do that, I shall be drowned in the cesspool!”

Now it came to pass that this nobleman, a valiant gentleman who had attended many imperial congresses and tournaments, was in the company of Emperor Henry VI at the imperial congress held in Erfurt in the year 1184. In attendance were also Landgrave Ludwig of Thuringia and Archbishop Konrad of Mainz, who had long been embroiled in a bitter feud and laid waste to each other’s lands.

In the presence of the emperor and many noble princes, counts, and lords, it was deemed necessary to reconcile these two antagonists in a hall of St. Peter’s Monastery. However, the floor of the hall was ancient and rotten, and it suddenly gave way under the weight of so many people. Beneath it lay a cesspool in which all the refuse from the secret chambers flowed together. Both Count Heinrich of Schwarzburg and Friedrich Count of Arnsberg fell into the putrid pit and met their miserable end. Gosmar Count of Hesse, Gottfried Count of Ziegenhain, Burgrave Friedrich of Kirchberg, Beringer of Meldingen, and others likewise perished in the disaster.

The emperor and the bishop had been standing in conversation in a window alcove and clung tightly to the iron grating, thus saving themselves. The Thuringian landgrave shared in the misfortune but escaped unscathed. Thus, the ominous oath of the Schwarzburger was fulfilled in a most lamentable manner.

The Historical Background

The legend we speak of is based on a historical event known as the Erfurt Latrine Fall (Erfurter Latrinensturz), which has been recorded in the history of the city. Although there is some debate over whether it was indeed a latrine that everyone fell into and whether it took place at St. Peter’s Monastery, it is widely accepted that the accident did occur.

The event took place in 1184 during the reign of Emperor Barbarossa. The Archbishop of Mainz, Conrad I, and the Landgrave of Thuringia, Ludwig III, were vying for control of the strategically and economically important city of Erfurt, which was located in the middle of Germany. As both men were important to the emperor, Barbarossa sent his son, Henry VI, to settle the dispute through diplomacy. At 19 years old, Henry had already been appointed as co-king, although he had not yet ascended to the throne of emperor. Despite his youth, he was politically experienced and promising.

At the time, Henry was on his way to Poland to wage war, but he stopped over in Erfurt as instructed by his father. While there, the collapse of the floor of a hall during a peace negotiation led to the deaths of several noblemen, including Count Heinrich of Schwarzburg and Friedrich Count of Arnsberg. The legend of Heinrich the Seventh and his prophetic phrase, “If I do that, I shall be drowned in the cesspool,” arose from this tragic event.

The place

The location where the court was held is a topic of dispute, with two possibilities being considered: the Petersberg or the Cathedral’s provostship of the Marienstift.

The Petersberg, situated on the outskirts of Erfurt’s old town, was initially a sacred site and a refuge, and it is believed that it also housed a royal palace. In 1060, a canon’s monastery was established there, which was later transformed into the Benedictine monastery of St. Peter and Paul. Following a fire between 1103 and 1147, the Romanesque St. Peter’s Church was reconstructed, becoming one of the city’s most magnificent structures next to the cathedral hill. The St. Peter’s monastery grew in prominence and became one of Thuringia’s most significant monasteries. Emperor Frederick I Barbarossa convened five imperial diets there, and Henry the Lion likely submitted to him in this location in 1181. As a result, it is probable that this would have been the location chosen by the young king.

However, there is also a possibility that the event took place at the cathedral provostry of the Marienstift. This building was notorious for its construction problems and it is written that the church collapsed in 1153 due to building weaknesses, which were a common cause of collapses in medieval Germany. Buildings during the Middle Ages were typically constructed using materials such as wood, stone, and clay, which were sturdy but prone to decay. Records show that several building collapses occurred in Erfurt during the Middle Ages, including the collapse of the city wall in 1226 and the collapse of several buildings during a fire in 1312.

Archaeological research at both locations has revealed many structural elements, but no gigantic cesspools. However, since the Peter’s Monastery has been built over with a fortress, even deep foundations have been destroyed in many instances. Therefore, further research is necessary to determine the exact location of the event.

The audience and the events

Who was present at the unfortunate latrine fall is still well known.

The question of whether the city should be ruled in the future by ecclesiastical or secular hands was of enormous importance for the nobility and high clergy of the wider area. Therefore, it is only logical that a large number of princes and bishops attended the event. Historical sources say that the room on the second floor of the building in question was so full that the beams could no longer bear the load.

So the accident was certainly a surprise, but a likely one. And apparently, it cost the lives of 60 people.

Luckily, the archbishop and King Henry had been in one of the window-niches at the moment of the fall, which saved their lives. While the floor beams broke and most of the assembly fell to the floor below, they were able to cling on. Due to the force and impact of the people and the building material, the dilapidated beams of the first floor also broke and the participants of the assembly fell – according to legend – into the “secret chamber” below, the cloaca. Henry found himself in an unfortunate situation and had to be rescued with ladders. His audience, however, met a much more unhappy fate.

Many lost their lives from falling beams and stones. Some drowned and suffocated in the feces. Landgrave Ludwig survived the incident and was saved but severely shaken.

Henry left in shock immediately after being rescued from this striking situation, leaving the locals to take care of rescue and emergency help.

What is interesting is not only the context and the accident, but also the place that is usually hardly mentioned in historiography: the “secret chamber”.

A gigantic loo?

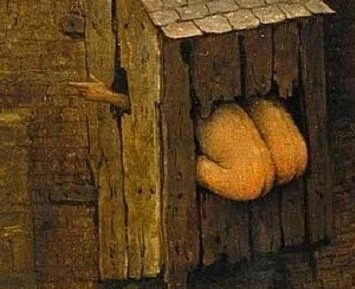

Some people doubt the legend’s account of the deadly cloaca, but huge privy pits were indeed commonplace in the Middle Ages. Almost every household had such a place below or behind its property. Therefore, we find distance regulations in the Sachsenspiegel, the applicable law book, which served to avoid disputes about the odor nuisance.

Sometimes the space used was a trench behind the houses, sometimes a canal, and sometimes a gigantic hole.

Today, such medieval cesspits provide researchers with information about the eating habits and hygiene standards of the time. A whole branch of archaeology has developed around this. For example, it has been found that almost all people at the time suffered from intestinal parasites because of these latrines. The worm eggs in the feces got into the groundwater and from there into the wells. Cleaning the pits was time-consuming and expensive, as it could only be done in winter and at night. That is why people waited as long as possible to call the disposal contractors of the Middle Ages. In some towns, the executioner was responsible for this task. Sometimes also water was diverted and led through the city to solve the problem. However, old account books show that some facilities were not emptied for decades.

While the famous Erfurt latrine has not been preserved, it is likely that it did indeed exist.

King Heinrich, who was lucky at the time of the accident, died later at not yet 32 years old, in Messina in 1197, after suffering from fever and severe diarrhea. No wonder, given the hygiene problems of the time, one might say.

Leave a comment