As most people know, Virgil (70-19 BCE) was a Roman poet renowned for his wonderful Bucolica, the enchanting Georgica, and the Roman national epic, the Aeneid. While today he is only acknowledged as a writer of nature and heroes, in olden times, and especially in the Middle Ages, he was considered above all a magician with a reputation for possessing special knowledge of the mystical and the occult.

This has long been forgotten and is today generally frowned upon as silly. You may wonder how a poet came to be associated with witchcraft.

But indeed, numerous historic legends about Virgil report how he controlled the elements, summoned spirits and performed feats of divination. Some of these stories sound like replicas of similar tales attributed to diverse saints and oriental heroes, others hint at traces of ancient Latin mythology.

To give an example, one of the most famous stories about Virgil’s supposed magical powers is the legend of the flycatcher. According to the tale, a group of builders were constructing a temple in Naples, but no matter how hard they worked, their progress was impeded by swarms of flies. Virgil supposedly came to the site and used his powers to create a magical bronze flycatcher that attracted all the flies away from the workers and the construction site.

Another legend involving Virgil is that of the talking head. According to the story, a man came to Virgil seeking his help to recover a lost treasure. Virgil agreed to help the man and instructed him to decapitate a corpse, which he then brought to Virgil’s laboratory. There, Virgil supposedly placed the head in a special container and performed a ritual that caused the head to come to life and reveal the location of the treasure. This head can still be seen in a painting by Girolamo Mocetto from the school of Mantegna.

According to further stories, Virgil was believed to have had the ability to control the elements. He supposedly calmed a storm by speaking to the wind and waves, allowing a ship to reach its destination safely. Virgil was also said to have been able to create powerful illusions and supposedly fashioned a garden that appeared to be filled with fruit trees and flowers, even though it was just an empty courtyard. This story even made it to Richard Wagner’s Parsifal when the magician Klingsor, Virgil’s supposed grandson according to Wolfram von Eschenbach, brings the young knight to such an enchanted garden.

Today, we wonder how the poet ever came to be associated with such abilities.

The idea of setting up the image of a fly to drive away flies reminds us of a Babylonian story, for in Lenormand’s Chaldæan Magic we are told that demons are driven away by their own images, and Beelzebub, as chief of flies, was the first to be mentioned in this regard. Other legends remind us of stories about Buddha, King Salomon and various Christian saints.

While Virgil may as a Neopythagorean have been interested in the occult and esoteric, there is no evidence to suggest that he actually practiced any magic.

Yet, to begin following the trail of evidence, it shall be said that Virgil is not entirely innocent in creating the myth.

This is due to the fact that Virgil called himself a ‘vate’.

‘Vate’ is a word that was used in ancient Rome to refer to a poet with divine or prophetic inspiration and tasks. The word *wātis (Latin vatis, Greek ouateis) is of Gallic origin and refers to a diviner, a prophet or an oracle. The root *wātis also gave the Germanic Wotan (Odin in Scandinavian). In ancient Latin text the term is found in Strabo (IV, 4, 4), Pliny (Natural History XXX, 13), Lucan (Pharsalus I, 448), Ammianus Marcellinus (XV, 9) and, before him, Timagena.

From these sources, it can be inferred that in ancient Rome, poets/vates were seen as intermediaries between the gods and humans. They were thought to possess special insights into nature and abilities that allowed them to communicate with the divine realm. Their poems served a purpose, as they were used to enchant nature, aid in agriculture, and even train horses with music. However, the term “vate” had fallen out of use by Virgil’s time, yet he referred to himself as such.

Virgil became well-known for his descriptive and vivid portrayals of the natural world that seemed enchanting. His Georgica paid tribute to the beauty and complexity of nature and contained detailed descriptions of agriculture, animal husbandry, and rural life in wonderful rhymes. Although these themes may appear peculiar for a poet who became the national bard of the ancient empire, nature held great significance for the ancient Romans.

In Roman times, nature was often associated with magic and mystery. Romans believed that the natural world was imbued with spiritual and divine forces and was the source of many of life’s mysteries and wonders.

One of the most significant natural phenomena was the cycle of the seasons, which was seen as a powerful symbol of the cycle of life and death and was celebrated in festivals and rituals. The Saturnalia and Lupercalia, for example, were both closely tied to the changing of the seasons and the rebirth of nature.

The Romans also believed in nature spirits, or “numina,” which were thought to inhabit the natural world. These spirits were associated with specific natural features such as trees, rivers, and mountains and were believed to possess magical powers that could be harnessed through ritual and prayer.

Thus, for Roman ears, Virgil sang in his poems about the mysterious forces that were closely tied to their spiritual and religious beliefs. He soon gained a reputation as a prophetic figure, and his poetry was seen as containing insights and predictions about the future. This status was enhanced by Virgil’s association with the legendary prophetess of the Sibyl.

In his most famous work, the Aeneid, he tells the story of the Trojan prince Aeneas and his journey to Italy, where he founds the city of Rome after descending into the Hades guided by the Cumean prophetess. In addition to the Aeneid, Virgil’s other works were also seen as containing prophetic elements. For example, his collection of pastoral poems, the Eclogues (or Bucolica), was believed to contain hidden references to the political and social climate of ancient Rome, and some readers saw even hints of future events, particularly the birth of Christ.

The “Sortes Virgilianae” (Virgilian Lots) became a popular form of divination in 2nd century Rome, only 100 years after the death of Virgil. The practice involved using a copy of Virgil’s works to ask a question or seek guidance and then opening the book at random and interpreting the passage that was revealed.

To perform the Sortes Virgilianae, an individual would first formulate a question or problem that they needed guidance on. They would then open a copy of Virgil’s works at random, and the passage that they landed on would be interpreted as a response to their question. The interpretation was often done with the help of traditional methods of divination, such as reading the passage in conjunction with other symbols or signs.

The Sortes Virgilianae were considered a form of divine revelation and were used by many Romans, and most famously Roman Emperors, as a way of seeking guidance and insight into their lives.

Augustus is said to have consulted the Sortes when deciding whether to spare the life of his friend and advisor, Marcus Agrippa. According to legend, Augustus opened Virgil’s works to a passage that praised the virtues of friendship, which he took as a sign to spare Agrippa’s life. Hadrian, Quintillus, and others also sought the famed poet’s advice.

The practice was popular until the late Middle Ages. Charles I of England is said to have been foretold of his decapitation by Virgil. According to legend, he consulted the Sortes Virgilianae and opened Virgil’s works to a passage that contained a line announcing impending doom. It is uncertain whether this was Dido’s prayer “Nor let him then enjoy supreme command, but fall, untimely, by some hostile hand,” or “Et sic in fatis” – “And thus it is in the fates.” In any case, legend has it that Virgil’s prophecy was correct.

While Virgil may have presented himself as more than just a poet and simple entertainer for fancy, there is a question about the origins of the more outrageous magic powers later attributed to him by completely different styles of tales.

In medieval times, Virgil was said to have created aqueducts, cut tunnels through mountains, or defended cities with a flick of his wand.

The enchanted garden in Wagner’s Parsifal was created by Klingsor, the said ‘grandson’ of Virgil.

The fault may lie with king Roger II, a Norman who was the King of Sicily from 1130 to 1154. Roger was a great admirer of Virgil and believed that the poet’s remains had the ability to protect the city of Naples, where the vate lay buried.

According to legend, while besieging Naples, Roger II visited the tomb of Virgil and instructed his court scholars, many of whom were Englishmen from the closely linked English Norman court, to study Virgil’s works and uncover the secrets of his ‘magic’. Roger II’s faith in Virgil’s abilities was not uncommon during medieval times, when many believed in the existence of supernatural powers and the capacity of certain individuals to wield them. This belief may have been strengthened by local Neapolitan lore. Additionally, it should be noted that Virgil was considered the greatest of all poets at that time, as Homer’s works were only translated into Latin in the 14th century.

Roger II’s admiration for Virgil solidified the poet’s reputation and may have inspired the English and German scholars at his court, including Conrad von Querfurt, Gervase of Tilbury, Alexander Neckham, and John of Salisbury.

Research suggests that this may have led somewhere among these to the attribution of the – probably freely invented – book of the Ars Notoria to Virgil. This medieval grimoire, or ‘book of magic’, was attributed to the poet, and is first proven to have existed around the times of Roger II.

According to legend, the famous oeuvre was written by Virgil as a means of obtaining knowledge and wisdom through the use of magical invocations of the death, i.e., necromancy.

The remaining little over 50 copies of the Ars Notoria reveal it to be a complex and esoteric text intended to provide the reader with a means of attaining spiritual enlightenment and knowledge of the divine. It contains a series of invocations that are supposed to unlock the secrets of the universe and enable the user to communicate with demons, angels, the dead, and other supernatural beings.

Despite its dubious authorship and the fantastical nature of its contents, the Ars Notoria was widely read and studied by medieval scholars and magicians, and it continued to be influential in later centuries until the Inquisition condemned most of the copies in circulation to be burnt.

It is most likely that the attribution of the Ars Notoria to Virgil was a deliberate invention by its medieval authors to lend the text more credibility and authority.

However, it is also possible that the attribution to Virgil was based on a genuine belief that the poet had magical powers or was somehow in tune with supernatural forces. The variations of the legend show that there was a belief in the connection of the book to someone “higher up” in the mystic hierarchy.

Sometimes it is indeed claimed that the Ars Notoria was not written by Virgil but either by the biblical King Solomon or by the centaur Chiron, and that Virgil only obtained it from one or the other of them. According to these versions, Virgil’s head was in his tomb lying on the book, and a certain Ludovicus, cousin of the famous Thomas Becket (who had indeed lived for years at the court of the Italian-Norman royal family), had taken it out to practice necromancy, while Virgil’s bones were brought to the Castel del Ovo in Naples and were never seen again.

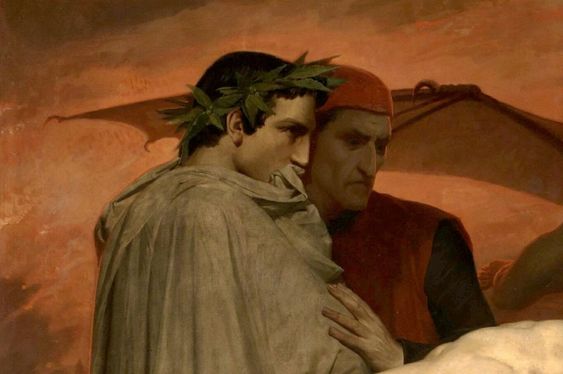

Given the fact that there circulated from then on numerous legends about Virgil and his magic powers it is surprising that Dante does not reflect any of these in his Divine Comedy. In Dante’s work Virgil represents reason and shows his medieval follower through the inferno. Virgil described the nine circles of hell in the Aeneid and Dante thus acknowledges his source. Yet, he does so without mentioning any magic.

The reason for this absence may be that the lore of magic was actually created by the German and English nobles who had picked up the idea at the court of King Roger II and took it home. It may have taken some centuries for the tales to return to Italian soil.

From there, it first spread before dissipating. Today, we no longer remember any of the magical mysteries of the vate.

All that remains is a contortion of the name of the poet. “Virgil” is more commonly used in modern English, while “Vergil” is a more archaic spelling. The actual name of the famous Roman poet was, however, Publius Vergilius Maro. The ‘I’ might have replaced the ‘E’ when the story of the magic powers came up, as Virgil carries an echo of the Latin word for ‘wand’, the virga.

“Forsan et haec olim meminisse iuvabit” – “Perhaps someday it will be pleasing to remember even these things.”

Aeneid, Virgil

Leave a comment