One of the most famous palaces in the world remains inaccessible to this day, buried under the southern Naples volcano, Mount Vesuvius. No one can visit it, and its secrets have yet to be fully uncovered. It’s possible that its owner is still buried within its ruins. One can only wonder who this unknown multimillionaire of antiquity was who owned the sunken splendor and what tragic story remains hidden under the lava on the slopes of Mount Vesuvius.

The most famous villa in the world

The palace, the Villa of the Papyri, is an enormous Roman complex discovered in the 18th century right next to the buried ruins of the Roman city of Herculaneum.

It lies buried deep in the tuff, trapped under six mudslides that Mount Vesuvius spewed over the coast near Naples in the year 79. The ruins of the palace were discovered in 1750 by Swiss Karl Weber and commissioned by the Spanish Bourbon kings. The exploration was conducted from the bottom of local wells through narrow tunnels in the brittle stone.

The villa got its name after charred scrolls were found in a small annex of the main building. To this day, they remain the only completely preserved library from Roman times ever found. Since papyrus does not last more than one or two centuries under normal circumstances, only a few scrolls have been preserved. In the villa, they survived as charcoal blocks, which are, however, difficult to read.

What was also recovered from the villa, which remains buried today, kept the world in suspense over the centuries: in addition to the papyri, the most precious mosaics, frescoes, and furniture were found, and above all, an incomparable collection of otherwise rare ancient bronzes.

Although the villa was split in the center due to the force of the waves of mud and lava that fell upon it and has never been fully excavated to this day, it has inspired the world. Films, books, and exhibitions have been created in its honor. In the National Museum of Naples, a room is dedicated solely to the mosaic floor of its Belvedere, and the Getty had his museum in Los Angeles built in its image. What he didn’t know is that he was following an incomplete model. It was not until much later that an immense trench was dug down to the ancient beach and it was discovered that the villa had multiple floors. Both its discoverer Weber and Getty had assumed that it only had a one-story main building with a loggia. However, it was located on a slope and had not only two lower floors, but also a swimming pool by the sea. All of this still lies walled in the tuff to this day, and nobody has yet touched the biggest part of the villa.

Recently, a trunk with textiles was found, and it is known that the lower floors contain clothing, furniture, and other items. However, the trunk was once again walled up. Further exploration seems too costly, too risky (in terms of conservation and stability), and to make matters worse, there are still inhabited buildings above the villa.

Yet, one question remains unanswered after all the research and studies: who lived in the villa at the moment of its demise? There is circumstantial evidence in this criminal case, and I take the liberty of discussing it here. All of this comes with the caveat that what follows is a hypothesis… albeit an intriguing one.

The clue of the charred library

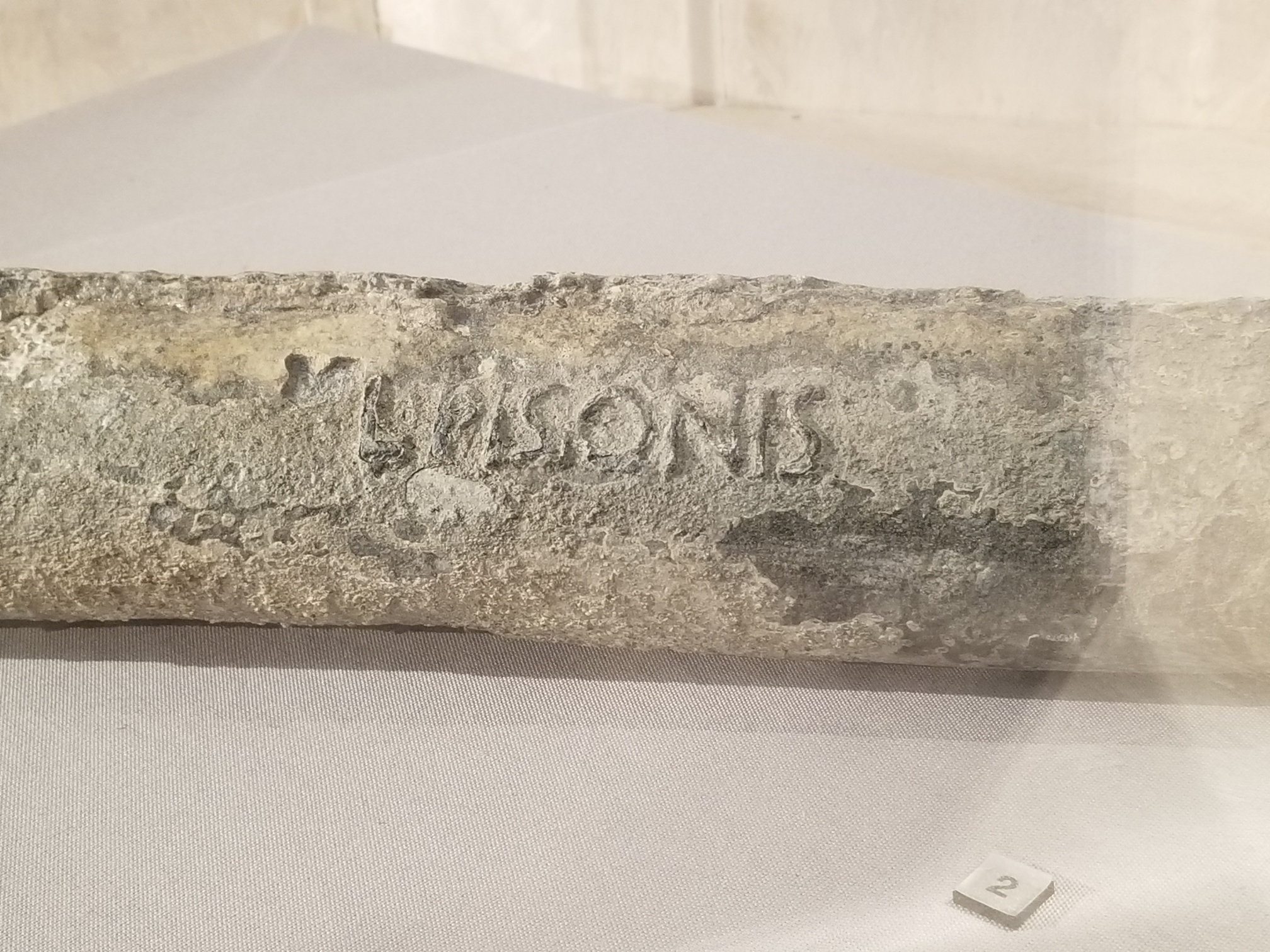

The villa may have originally belonged to Piso and is therefore still referred to as Piso’s villa. However, Piso died long before the villa was buried, so he could not have been living in it at the time of its demise. Recent research in the waters off Baia, north of Naples, has identified a villa whose plumbing is clearly stamped with the name Lucius Piso. This may not be sufficient to rule out Piso’s connection to the villa in Herculaneum as there were several Lucius Pisos. However, given that Baia was close to Caesar’s villa, now the castle of Baia, Piso may have preferred a villa in Baia for political calculation and prestige.

It is possible that the Piso library was inherited by Piso’s daughter, Calpurnia, who was given as a bride to the aging Caesar at the age of 17 and became a widow just a few years later. There are theories that Caesar originally had the villa of papyri confiscated by one of his political enemies. This would have given his wife the right to live in the villa after his assassination, even though it is unlikely that she would have inherited it under Roman inheritance law. The villa would likely have remained in the possession of Caesar’s family, the Julii.

However, this would explain the presence of the library. Such a place of residence would not be improbable for Calpurnia. Nero’s wife Poppaea Sabina lived only a little further in Oplontis in a villa also buried by Vesuvius long after her death.

The question remains, who was living in the Villa of the Papyri when it sank. Someone who was certainly wealthy, but probably also someone who, as mentioned above, was close to the imperial family. The dynasty of the Julians ended with Nero’s suicide, and their property passed to the new emperor Vespasian, and then to his son Titus, who was the emperor at the time when Herculaneum sank.

Can we assume that the villa belonged to Emperor Titus? At the very least, it is a possibility.

Circumstantial evidence: The letters of Pliny

There is other circumstantial evidence and we find it in the two world-famous letters of Pliny the Younger, which he wrote to the historian Tacitus thirty years after the sinking of Herculaneum. In these, the young Pliny describes how his uncle, Pliny the Elder, died. Pliny the Elder was not only a great naturalist, but also an admiral of Rome’s fleet and a close friend of the emperor. He perished while trying to bring a desperate rescue to the coast buried by Vesuvius. What we know of his death, however, is blurred by the turmoil of time.

On one hand, his nephew described the events from hearsay and after a long time. On the other hand, he wrote in Roman capital letter script on papyrus, which was teeming with abbreviations and punctuation had not yet been invented at that time. Therefore, only four contradictory copies have survived. While they provide some insights, they also create misunderstandings.

For example, Pliny the Younger writes that his uncle received a letter on the day of the catastrophe asking him for help, and he then set the emperor’s fleet in motion. The few versions of the story diverge as to who sent this letter and where Pliny went. A friend, a certain Rectina, whose husband was a Tascus or Cascus, appears several times in the interpretations as the sender.

However, upon closer examination, it appears to be an improbable scenario that the translators are attempting to convince us of.

For one thing, it is unlikely that an admiral like Pliny would have had the authority to rush to the aid of an insignificant friend with the imperial fleet. On the other hand, it is remarkable that this friend would have possessed carrier pigeons from the emperor’s troops. However, how else could the message have been delivered, with the sea in turmoil and the wind blowing against the coast?

It is therefore much more likely that Pliny was summoned to help by someone in command or with the authority to dispose of power and soldiers. Already Winkelmann noted that the place built much later over the lava fields of the site of the ancient ruins was called Resina. It was renamed only after the excavations in Herculaneum. From Rectina to Resina, the transition is not far, even though this conclusion has been contradicted for linguistic reasons. Nevertheless, I still believe that Pliny the Younger is referring to the place or villa Rectina, not a person. A grammatical form in the letter (in the small word exterritae) suggests that the writer was a woman.

It can be assumed – without being entirely certain – that Pliny was called to help from the Villa of the Papyri or a nearby structure. Pliny went to Rectina and attempted to land on the beach of Herculaneum. The Villa of the Papyri had only a small private harbor. Furthermore, hundreds of dead bodies were discovered in the boat hangars of Herculaneum, and in front of them, an overturned boat and the body of a Roman legionary.

All of this paints a picture of a dramatic rescue attempt that Pliny had to abandon with burning sails. He remained trapped on the coast since, in antiquity, ships could not sail back against the wind. Finally, he perished from poisonous gases in Stabiae, where he had fled.

Meanwhile, in Herculaneum, the volcano engulfed the city and nearby villas, causing the ground to sink four meters lower. Waves of mud rolled over everything.

When calm returned, the new beach was hundreds of meters further out to sea.

The evidence of the unpainted walls

After all of this, the question remains: who lived in such a richly furnished villa by the sea and had enough authority to call the fleet for help, and who took this secret to the grave?

One thing seems certain: the person remained unknown to the young Pliny even after the event. His uncle received a letter from (the place) Rectina, but the younger Pliny does not know who it was from. Otherwise, one might think, he would have mentioned it.

An additional circumstantial fact is that when the two still unknown floors of the villa were finally discovered in the 21st century, only a very small area of the second floor was excavated. In this area, they found something astonishing: the painted walls were as fresh and bright as if they had been decorated just yesterday, while the rest of the wall was white.

17 years before the fall of Herculaneum, it had already been damaged by a violent earthquake and apparently the villa was being restored at the moment of its fall.

And when does one usually restore? … When there is a new inhabitant. It could be, therefore, that the villa had just been taken possession of by an important person.

But who could have been this so rich and yet so secret new inhabitant who moved there just before the fall of Herculaneum? There is a promising candidate, and even a female one.

“Against her will and against his”.

The great Suetonius describes the life and the imperial coronation of Vespasian’s son and successor, the Emperor Titus, who ruled since June 24, 79. In doing so, he uses a famous line in reference to the accession: “Berenice he sent away from Rome, against her will and against his.”

Who was this Berenice and where did Titus send her?

Queen Julia Berenice of Judea was Titus’ form of Cleopatra.

Few other ancient figures – except perhaps the Pharaoh of Egypt herself – have inspired as many painters, playwrights, novelists and opera composers as this Berenice. See here the list of them.

Her unhappy affair with Emperor Titus, set against the dramatic background of the first Jewish-Roman war, became a symbol of the conflict between love and reason of state. In the process, Berenice’s figure was so idealized by the poets that today, it is hardly possible to recognize the historical person behind the legend.

Berenice was eleven years older than Titus and the granddaughter of the Herod from the Bible. At the age of 13, she was married to a wealthy Jew from Alexandria who died before they could consummate the marriage. Later, she married her uncle, Herod from Chalcis in Lebanon, and after his death, she lived with her brother, the new king Herod Agrippa II. The latter led to rumors of incest, which Berenice never got rid of, not even by quickly dissolving the marriage with Polemon of Cilicia (who, by the way, was a descendant of Marc Antony).

Since Berenice, like her brother, was on the side of Rome and even counted as a member of the house of the Julii, she incurred the wrath of her own people when the first Jewish revolt against Roman rule broke out in 66 AD. Initially, she tried to mediate, but an angry mob set fire to her palace and that of her brother, forcing her to flee with her treasures and bodyguard to the camp set up by the Romans outside the walls of Jerusalem.

It was in this camp that General Vespasian, who was the governor of Syria on behalf of Emperor Nero, and his son Titus arrived in 67 AD to put down the rebellion. And it was in Vespasian’s tent that the fateful encounter between Berenice and the young prince took place.

While Rome sank into civil war after Nero’s suicide, Titus remained in Judea, driven by “the extreme desire to see Berenice again,” because “his young heart was not insensitive to the charms of this queen,” according to Tacitus.

When Vespasian was proclaimed emperor, he received the support of Berenice and King Herod Agrippa, who themselves remained in Judea to support Titus in the suppression of their own people and to applaud the burning of the temple in Jerusalem.

After the end of the revolt, Berenice accompanied Titus to Rome, where they shared the imperial residence with the apparent intention of marrying. However, political problems soon arose. The Romans did not like the idea of a foreign queen marrying the heir to the empire. They could allow the concubinage of an emperor who was already the father of male heirs but not the concubinage of an unmarried prince in the prime of his life. They did not want a second Cleopatra.

Also Vespasian’s advisors tried everything to thwart the future emperor’s planned marriage to a foreign woman who was too old to bear children. However, Berenice achieved such great influence that Quintilian, an eminent lawyer at the time, reports a trial before Vespasian’s crown council, which concerned Berenice, and in which she herself sat on the panel of judges while he pleaded as counsel before it.

After Vespasian’s death in 79 AD, Berenice was with Titus, now emperor. But a marriage to the Oriental queen threatened political stability in the eyes of the Romans. Titus was forced to send her away against his and her will (invito, invitam, says Suetonius) because of the enormous public criticism.

Exactly when this happened is disputed. Yet, probably Berenice was banished from Rome immediately after Titus’ accession to power, which took place on June 24, 79. According to Pliny, the volcanic eruption happened on August 24, 79, although today we assume a somewhat later date.

Rejected by Titus, the woman who had already seen herself as an empress had to go into hiding. Her traces disappeared so completely from history that not even the date and circumstances of her death are known. Where did the Cleopatra of the new emperor disappear to? Do we really think, Titus would abandon the woman he loved so completely?

Did Berenice die in the Villa of the Papyri?

Let’s summarize the story again, which has been the inspiration for 40 operas and numerous plays, and has been written about by Corneille, Racine, and Mozart:

Berenice and Titus were in love, but their relationship was threatened by political instability. Berenice had no future in Judea, and Titus designated his brother Domitian as his successor.

Is it wrong to speculate that Titus may have hidden Berenice in the Villa of the Papyri?

This would explain the ongoing renovations, military presence, female letter-sender, and numerous art treasures found there.

Pliny, who would have been privy to the emperor’s secrets as an admiral of the fleet, may have rushed to the queen’s aid. May be Titus formed a commission to dig for goods and the dead in the cities on Vesuvius, to find and bury Berenice?

This is just speculation and remains uncertain. Titus died two years later, and his last words were “I have made only one mistake in my life.”

May be he wanted to say, that he committed the error to send Berenice to Herculaneum.

Read more in the archaeology-Thriller ‘From Hidden Places‘.

UC Ringuer