Beauty is said to be in the eye of the beholder. Nevertheless, it is astounding what people have done to themselves over time in the name of beauty. Pierced ears, lip plates, and full-body tattoos are just a few examples. Some of these beauty procedures cause direct harm to the individuals involved. Broken and filed teeth, unnaturally elongated necks, and bound feet were once considered beautiful by those who wore them, despite the pain they endured.

One particularly extreme form of body modification was the deformation of the head, inflicted by mothers on their newborn babies. Despite its bizarre cruelty, it appears to have been a surprisingly widespread tradition.

Since the media have publicized archaeological finds from Latin America that show skull deformations, more people are familiar with artificially bandaged elongated skulls from this region than with the traditions of other civilizations. This is partly because of the context of the bloody rituals of the Maya and Aztecs. However, this fashion was known all over the world.

As early as the 4th and 5th centuries, the Huns, Goths, and Alans in Europe practiced the deliberate deformation of their children’s skulls. Although only one image of Theodoric the Great, the King of the Goths, who dominated half of Europe in the 6th century after Christ, has survived, it shows him with round saucer eyes and a strangely high skull. Researchers have concluded from comparative grave finds of the Goths and this picture that Theodoric had a deliberately deformed skull. Strong head deformations, among other things, made the eyes stand out and could explain the representation of the ruler. Whether this conclusion is correct is uncertain, but it is possible that Theodoric was subjected to this practice as a child.

Numerous grave finds also support this theory and show the presence of the tradition in Europe. For example, in 2006, 64 archaeological finds with proven skull deformations were known from Germany, 15 from Switzerland, and 43 from France. The tradition lasted a long time and was even more widespread in some regions than the archaeological finds suggest.

At the end of the 19th century, the French Doctor Delisle thus reported skull deformations in the French departments of Haute-Garonne and Seine-Maritime. According to his estimates, 15% of men and 10% of women in the region had deformed skulls. These deformations were caused by traditional children’s hoods and headgear designed to protect the child’s skull from injury by tying and padding it, intentionally or unintentionally deforming it. Girls typically wore this headgear until they got married, while boys wore it until the age of eight. This tradition from the 14th/15th century likely originated in Belgium and was practiced in the regions of southern France until the end of the 18th century, and around Toulouse even until the beginning of the 19th century.

The method

Surprisingly, these deformations do not seem to be harmful. According to a scientific article from 2007 “there seems to be no evidence of negative effects on societies that have practiced even very severe forms of intentional cranial deformation”.

Nevertheless, the practice remains quite brutal. Radical head deformation must be performed early in life when the skull of an infant is still soft. The complex procedure usually begins shortly after birth and lasts several months, sometimes up to two years. The head shapes created by head fixation vary greatly from place to place, but they tend to fit a particular pattern at a particular time and place. The shapes range from high profiles with a flattening front to back to extremely long shapes. Soft bandages (usually made of fabric) are almost universally used to change the shape of the head, and in many cases, pieces of wood are used to flatten the shape in the desired places.

Since artificial skull deformation requires months of head binding, its origin is puzzling. What is even more puzzling is that this cultural practice has clearly originated independently in numerous places around the world. Although some traditions may have spread through migration, as suggested for the Bering Strait migrants who populated the American continent, it developed in many other places in isolation and without any historical reference.

Examples of deliberate deformation are known from Africa, China, America and Europe.

Not only in Europe, also throughout America and in various indigenous tribes, the heads of infants were formed by their parents through bandages. Evidence of this can be found in Mayas, Incas, Choctaw and Chinookan. The reason for this must have been the attempt to secure a good social position for the child and to make it beautiful. According to Gonzalo Fernandez de Oviedo, a Spanish chronicler of the conquest of America, in fact a Maya declared: “This is because our ancestors were told by the gods that if our heads were so shaped, we would appear noble…”.

In Mayan culture, two types of artificial skull deformation were common. Those children who were destined to occupy a high-ranking position were given so-called “oblique deformations”, which led to a high, pointed head shape. The general population could only use an “upright deformation” that resulted in a rounded skull shape with a flattened side. Whether these forms were adopted in the style of the skull of a jaguar or corn god is controversial among historians and archaeologists.

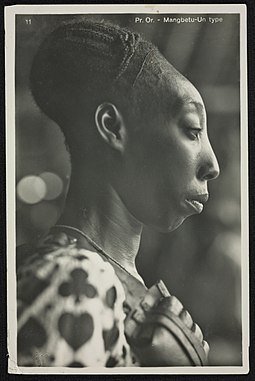

The practice was also to be found in Africa. The Mangbetu tribe in the Congo, for example, carried relatively spectacular tower skulls for several generations. As a cultural identity mark and sign of tribal affiliation, a skull deformation was carried out in infants, especially among higher tribal families, by tying them together with braided lianas over a period of more than a year. According to the Mangbetu, this should also improve the ability to think and learn. In the 1950’s, the tradition began to disappear with increasing contact with Western culture.

For us the high skulls of the babies on the old photos seem today frighteningly cruel. But at a time when beauty fanatics have ribs surgically removed and noses reduced, who knows when skull deformation will come into fashion again.

Head fixation in Ancient Egypt?

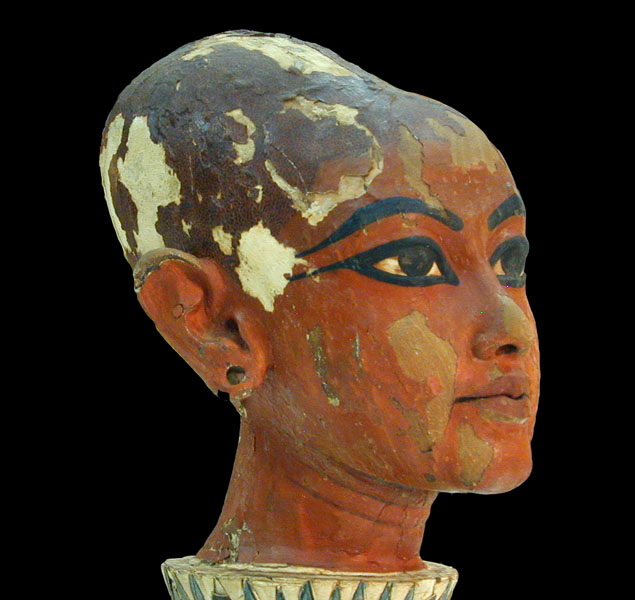

Remains the question of whether head-binding also occurred in ancient Egypt, as has been suggested, especially during the 18th Dynasty. Wall paintings and sculptures depict the famous Akhenaten, Nefertiti, and their children with unusually long head shapes. Through the study of their mummies, it has been confirmed that they had elongated skulls, a saddle-shaped depression on top, and a corresponding recess at the base, all of which correspond perfectly to the well-documented characteristics of head-binding in other regions.

While scientists at the Field Museum are sure that this indicates head-binding, there is no written evidence for this. In fact, other Egyptologists have generally rejected the possibility of head-binding in ancient Egypt. The elongated heads in wall paintings and sculptures are interpreted as stylistic exaggerations and artificial skull formations are excluded, as no records of such a practice were found. The appearance of strangely shaped skulls is, in their opinion, probably due to health reasons.

The question of head deformation in ancient Egypt remains unsolved for the time being, although the striking skull shapes of Akhenaten and Tutankhamun provide tempting clues. Recent scans of later Egyptian mummies carried out at the Field Museum have shown that Minirdis, the son of a stolistic Akhmim priest, also had a slight skull deformation. Perhaps this cultural practice occurred during the early Ptolemaic period in Akhmim, which was an important religious center. It has been suggested that the deformation of the skull was done in Egypt secretly to avoid revealing that it was human-made, rather than proving the special origin of the bearer.

U.C. Ringuer

Reblogged this on Die Goldene Landschaft.

LikeLike